How the Greedy Algorithm Shapes Miner Rewards in Blockchain Networks

Table of Links

Abstract and 1. Introduction

1.1 Our Approach

1.2 Our Results & Roadmap

1.3 Related Work

-

Model and Warmup and 2.1 Blockchain Model

2.2 The Miner

2.3 Game Model

2.4 Warm Up: The Greedy Allocation Function

-

The Deterministic Case and 3.1 Deterministic Upper Bound

3.2 The Immediacy-Biased Class Of Allocation Function

-

The Randomized Case

-

Discussion and References

- A. Missing Proofs for Sections 2, 3

- B. Missing Proofs for Section 4

- C. Glossary

\

2.3 Game Model

We examine a game between an adversary and a miner. This perspective aims to quantify how much revenue the miner may lose by the miner’s incomplete knowledge of future transactions when allocating the currently known transactions to the upcoming block. In this regard, the users active in the system can be thought of as an adversarial omniscient “nature”, that creates a worst-case transaction schedule. An allocation function has no knowledge of future transactions that will be sent by the adversary, and so optimal planning based on the partial information that is revealed by previous transactions may not be the best course of action. However, somewhat surprisingly, we later show that it is in fact so. Given a miner’s discount rate, there is a conceptual tension between including transactions with the largest fee and those with the lowest TTL. Thus, the quality of an allocation function x is quantified by comparing it to the best possible function x′, when faced with a worst-case adversarial ψ. The resulting quantity is called x’s competitive ratio. To remain compatible with the literature on packet scheduling, we define the competitive ratio as the best possible offline performance divided by an allocation function’s online performance, rather than the other way around, and so we have Rx ≥ 1. An upper-bound is then attained by finding an allocation function that guarantees good performance, and a lower-bound is attained by showing that no allocation function can guarantee better performance.

\ \

\ \ \

2.4 Warm Up: The Greedy Allocation Function

The Greedy allocation function, defined in Definition 2.6, is perhaps a classic algorithm for the packet scheduling problem, and was explored by the previous literature for the undiscounted case. Moreover, empirical evidence suggests that most miners greedily allocate transactions to blocks. Previous works show that in Bitcoin and Ethereum, transactions paying higher fees generally have a lower mempool waiting time, meaning that they are included relatively quickly in blocks [MACG20; PORH22; TFWM21; LLNZZZ22]. Indeed, the default transaction selection algorithms for Bitcoin Core (the reference implementation for Bitcoin clients) and geth (Ethereum’s most popular execution client), prioritize transactions based on their fees, although the default behavior of both can be overridden. It is thus of interest to see the performance of this approach.

\ Definition 2.6 (The Greedy allocation function). Given some transaction set S, the Greedy allocation function chooses the highest paying transaction present in the set S, disregarding TTL:

\

\ In case there are multiple transactions with the same fee, these with the lowest TTL are preferred.

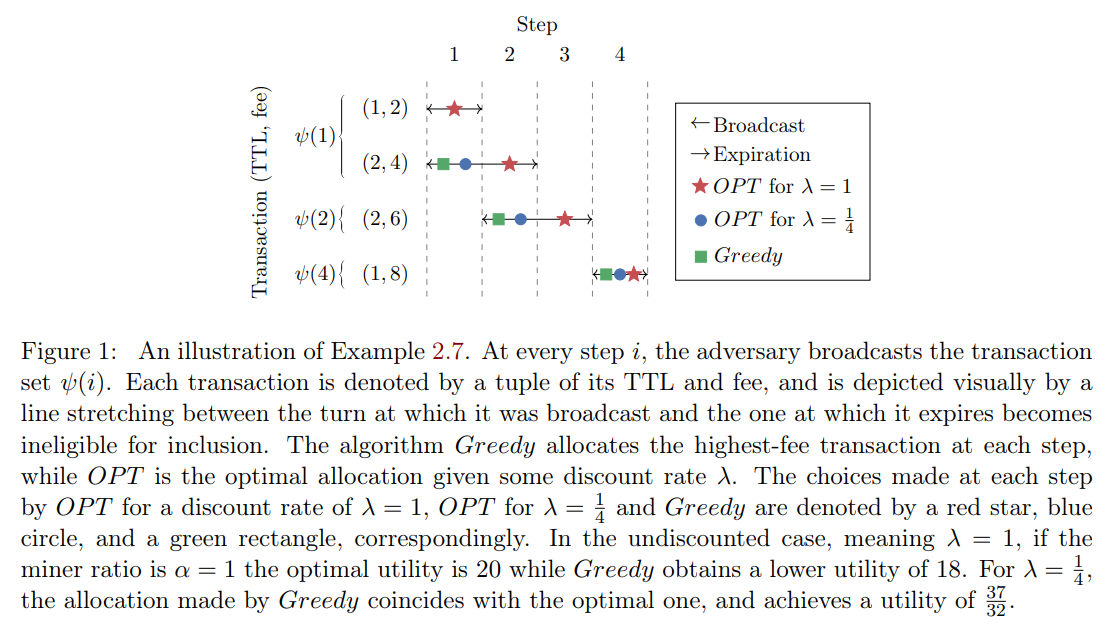

\ In Example 2.7, we illustrate how the performance of Greedy may depend on the discount rate.

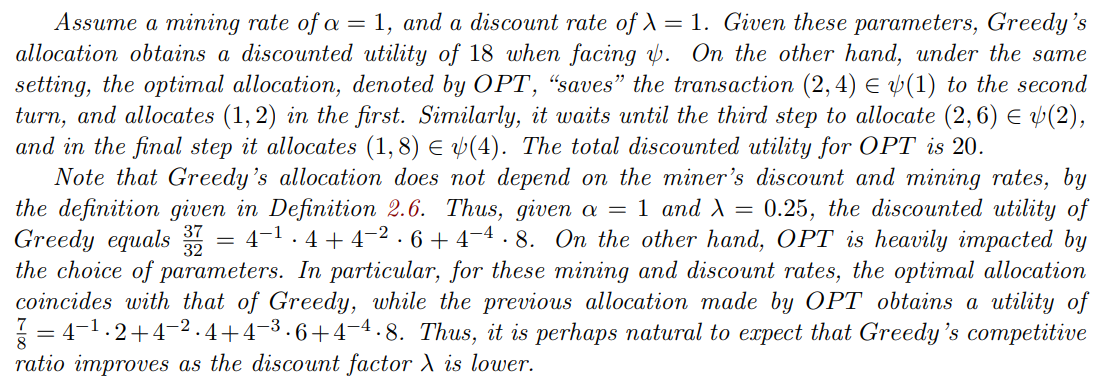

\ Example 2.7. We examine the performance of Greedy given the following adversary ψ.

\

\ The transaction schedule defined by ψ is depicted in Fig. 1. At turn 1 the adversary broadcasts two transactions: (1, 2) which expires at the end of the turn and has a fee of 2, and (2, 4) which pays a fee equal to 4 and expires at the end of the next turn. Because Greedy prioritizes transactions with higher fees, it will allocate (2, 4), while letting the other transaction expire. In the next turn, the adversary broadcasts a single transaction with a TTL of 2 and a fee of 6, which is the only one available to Greedy at that turn, and thus will be allocated. At step 3, the adversary does not emit any transactions, and on step 4, a transaction (1, 8) is broadcast and then allocated by Greedy.

\

\

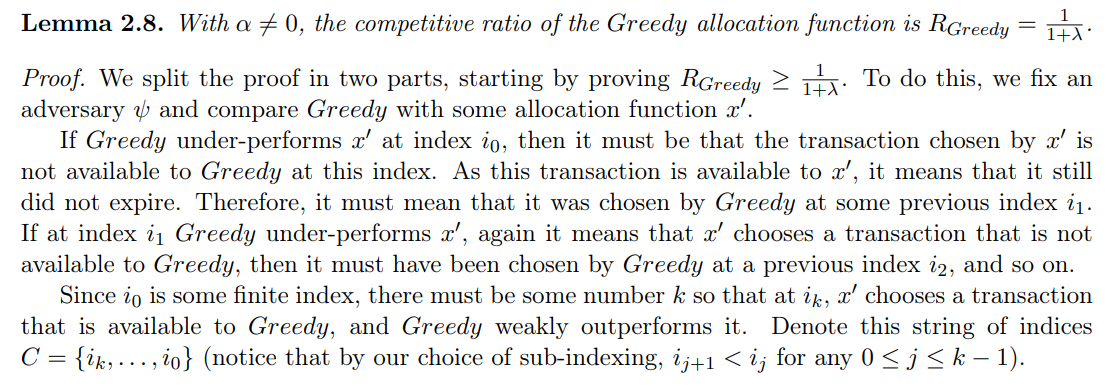

\ In Lemma 2.8, we bound the competitive ratio of Greedy, as a function of the discount rate.

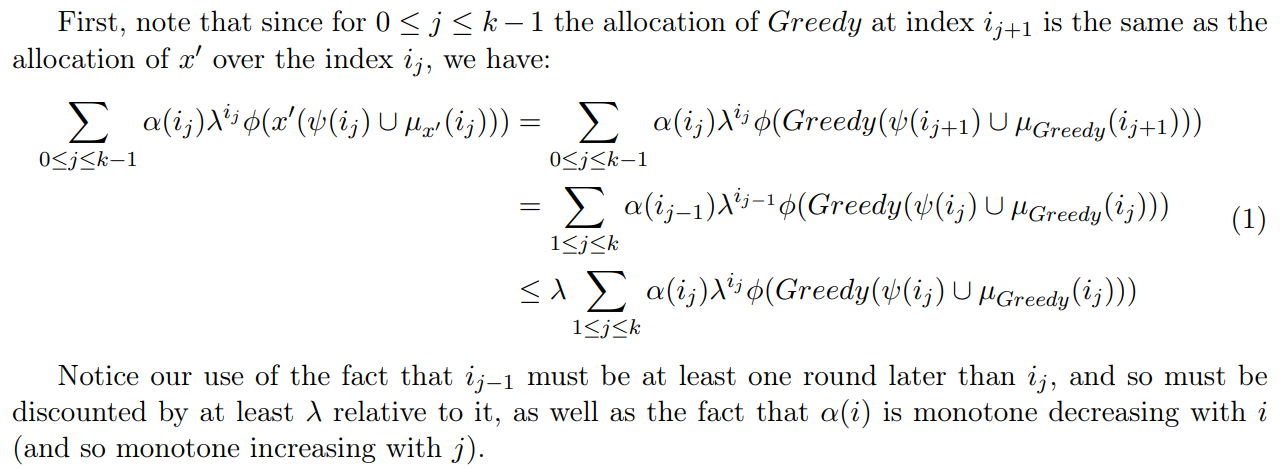

\

\

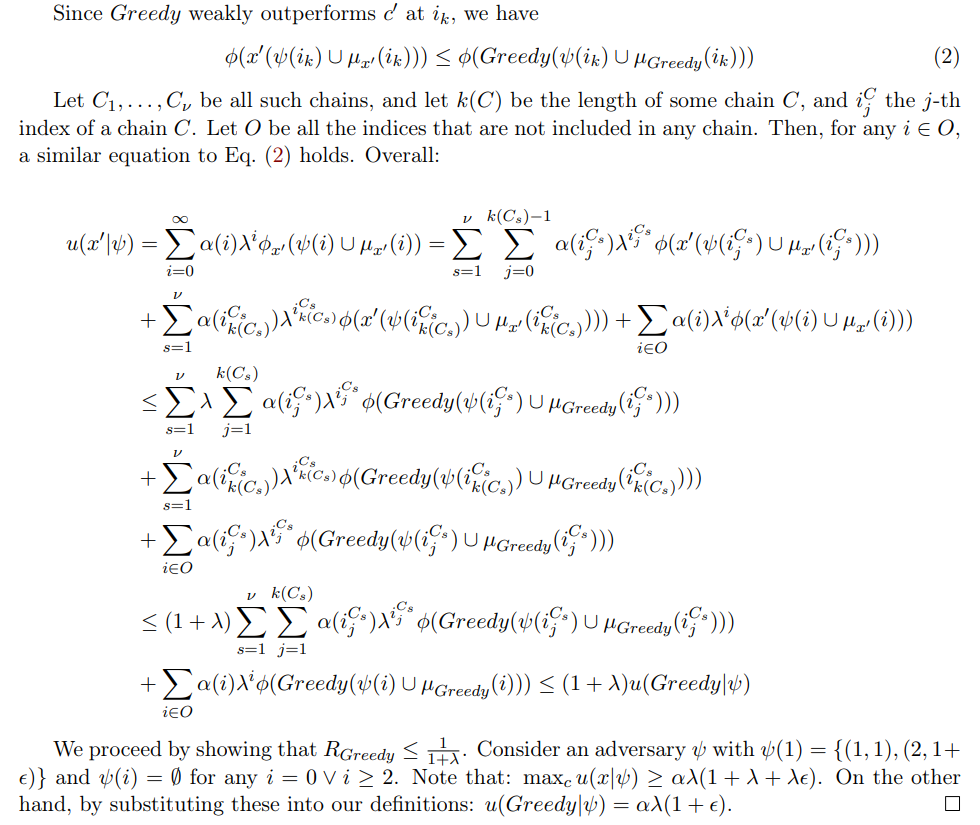

\

\

:::info Authors:

(1) Yotam Gafni, Weizmann Institute ([email protected]);

(2) Aviv Yaish, The Hebrew University, Jerusalem ([email protected]).

:::

:::info This paper is available on arxiv under CC BY 4.0 DEED license.

:::

\

You May Also Like

US Stocks Surge Higher: S&P 500 and Nasdaq Lead Market Rally with Solid Gains

Pentagon claims it's 'only just begun to fight' as Trump says Iran war 'very complete'