Must Read

In the global race to decarbonize, the most successful economies learned that the energy transition fails when it competes with the dinner tableIn the global race to decarbonize, the most successful economies learned that the energy transition fails when it competes with the dinner table

[Vantage Point] The Leviste sting: The risks of trading farmland for megawatts

This column examines why converting productive farmland into solar sites carries long-term economic risks that often outweigh short-term energy gains, drawing on global experience from Japan, Europe, and the United States. We argue that utility-scale solar is far more land-intensive than commonly assumed, and that sacrificing prime agricultural areas weakens food security, raises inflation risks, and deepens import dependence.

Using the stalled projects and expansive land bank of Leandro Leviste’s Solar Philippines as a case study, the piece highlights how speculative energy development can tie up thousands of hectares without delivering promised capacity. The analysis underscores why the Department of Agriculture’s land-reclassification freeze reflects a necessary recalibration — one that recognizes farmland as strategic national infrastructure rather than expendable real estate in the energy transition.

The Department of Agriculture’s (DA) freeze on land reclassification was sold as housekeeping. It was anything but. It was a late but necessary admission that countries which sacrifice farmland to solar development end up paying twice — once in lost food security, and again in higher economic risk.

Global experience suggests that countries which treat productive farmland as a convenient site for energy infrastructure often discover — too late — that the real costs surface not on balance sheets, but in higher food prices, import dependence, and economic volatility. Renewable energy is essential to long-term competitiveness, but when it is built at the expense of food systems, it creates vulnerabilities that compound over time. The energy transition becomes fragile when it weakens the very supply chains that sustain households. (READ: EXPLAINER: What is just energy transition?)

The sting

This global lesson is already visible in the Philippine context. Solar Philippines, founded by Filipino businessman and Batangas Representative Leandro Legarda Leviste, assembled a land bank of roughly 10,000 hectares earmarked for solar parks across Luzon — an area comparable to a mid-sized city. At the same time, Solar Philippines’ key subsidiaries accumulated close to 12,000 megawatts in service contracts with the Department of Energy (DOE). Yet, execution fell far short of ambition. Only about 174 megawatts, or roughly 2%, entered commercial operation. Regulators have since moved to terminate contracts that cover more than 11,400 megawatts and pursue penalties reportedly reaching ₱24 billion. Beyond regulatory failures, the episode highlights a deeper risk: large tracts of land can be tied up for years in speculative energy development that never materializes, while alternative productive uses are foreclosed.

LAND. A Solar Philippines team, led by its founder Leandro Leviste (fourth from right) poses with a tarpaulin that says — “This has been acquired buy Solar Philippines. Got land for sale or lease?” The land is for the expansion of a SP New Energy Corporation (SPNEC) project, says a Solar Philippines social media post on December 31, 2022. Courtesy of Solar Philippines FB

LAND. A Solar Philippines team, led by its founder Leandro Leviste (fourth from right) poses with a tarpaulin that says — “This has been acquired buy Solar Philippines. Got land for sale or lease?” The land is for the expansion of a SP New Energy Corporation (SPNEC) project, says a Solar Philippines social media post on December 31, 2022. Courtesy of Solar Philippines FB

The opportunity cost is substantial. Hypothetically, if Leviste’s solar land footprint of 10,000 hectares were devoted to irrigated rice cultivation — at a conservative yield of eight tons per hectare per year — it could produce roughly 80,000 tons of rice annually. At around ₱30 per kilo, that equates to more than ₱2 billion in domestic food output every year. Over a typical project lifespan, before accounting for multiplier effects, foregone production could exceed ₱50 billion. Replacing that volume through imports would widen the trade deficit and expose consumers to external shocks.

The central misconception behind such outcomes is scale. Utility-scale solar is not a light user of land. International modeling shows that meeting even moderate solar targets can require between 1.2% and 5.2% of national land area in land-constrained countries, such as Japan and South Korea, and up to 2.8% in parts of Europe. These are not marginal footprints. They translate into tens of thousands of hectares — precisely the flat, irrigated, and accessible parcels that agriculture also depends on the most.

In theory, energy planners assume that solar will be placed on “available” land. In practice, developers gravitate toward areas with road access, stable terrain, proximity to transmission lines, and minimal legal disputes. Those characteristics describe productive agricultural plains, not wastelands. Over time, energy infrastructure and farming compete for the same geographic advantages.

Countries that tolerated this overlap paid for it. Japan’s post-Fukushima solar boom, fueled by generous feed-in tariffs, made leasing farmland for panels more profitable than planting rice. Rural land markets tilted toward energy production. Within a decade, domestic output weakened and rural food security deteriorated, forcing regulators to tighten zoning rules. Germany and Italy followed a similar arc. Today, the European Union prioritizes rooftops, brownfields, former mines, and industrial zones for solar, treating productive farmland as strategic infrastructure rather than spare capacity.

Agriculture creates jobs

The economics explain why this matters. A single gigawatt of utility-scale solar can require 1,000 hectares or more. Once installed, panels lock land into a single, low-employment use for 25 to 30 years. Agriculture, by contrast, is labor-intensive and multiplier-rich. It sustains rural employment, supports logistics and processing industries, and stabilizes domestic demand. Every hectare removed from food production tightens supply, amplifies price volatility, and increases exposure to global shocks — from climate disruptions to export bans.

For a net food-importing country like the Philippines, that vulnerability compounds quickly. Higher import dependence transmits global price swings directly into inflation. It widens the trade deficit and pressures foreign exchange reserves. Over time, it weakens monetary policy flexibility. Land use, in this sense, becomes part of macroeconomic management.

Even in land-rich economies, the pattern is visible. In the United States, renewable energy facilities already occupy more than 420,000 acres of rural land. While this represents a small share of total farmland, these projects cluster on prime, well-located parcels. Location matters more than percentage. Losing high-quality land weakens food systems far more than losing marginal acreage.

Solar Philippines announces on May 17, 2023 that SP New Energy Corp. had acquired a first batch of solar projects from its parent firm, Solar Philippines, including the expansive Tarlac Solar Farm, as shown in this image. Courtesy of Solar PH Facebook

Solar Philippines announces on May 17, 2023 that SP New Energy Corp. had acquired a first batch of solar projects from its parent firm, Solar Philippines, including the expansive Tarlac Solar Farm, as shown in this image. Courtesy of Solar PH Facebook

Agrivoltaics

Proponents of farmland-based solar often cite agrivoltaics as a compromise. Global data urge caution. Agrivoltaics is the practice of installing solar panels above or alongside crops so the same land produces both electricity and food. This dual-use systems may work for high-value specialty crops in temperate climates, but they are far less effective for staples, such as rice and corn, which depend on full sunlight, mechanization, and predictable water management. In developing economies, agrivoltaics often becomes farmland in name and energy infrastructure in practice.

There is also a distributional dimension. Solar developers secure long-term, often dollar-linked returns. Investors enjoy predictable cash flows. Farmers receive fixed lease payments and surrender generational assets. Local governments gain short-term investment optics. Consumers absorb higher food prices. What emerges is not inclusive green growth, but a quiet transfer of risk from energy producers to households.

The DA’s moratorium reflects an understanding that land conversion is not a neutral planning exercise. It is a macroeconomic decision with consequences for inflation, foreign exchange stability, and social cohesion. Preserving agricultural land is equivalent to preserving buffers against food price shocks — buffers that no amount of imported power can replace.

None of this is an argument against solar power. It argues against undisciplined siting. The Philippines has vast untapped potential on rooftops, commercial estates, transport corridors, reservoirs, and degraded lands — spaces where renewable energy adds value without subtracting from food security. Choosing prime farmland instead is not efficiency. It is expedience.

In the global race to decarbonize, the most successful economies learned that the energy transition fails when it competes with the dinner table. Protecting farmland is not resistance to progress. It is the foundation of economic resilience in an increasingly unstable world. – Rappler.com

Sources and references for this column include data and policy materials from the Department of Energy, the European Union energy and land-use policy framework, the United States Department of Agriculture, and international renewable-energy and land-use studies, alongside publicly available company disclosures and regulatory filings related to major Philippine solar project.

Click here for other Vantage Point articles.

Disclaimer: The articles reposted on this site are sourced from public platforms and are provided for informational purposes only. They do not necessarily reflect the views of MEXC. All rights remain with the original authors. If you believe any content infringes on third-party rights, please contact [email protected] for removal. MEXC makes no guarantees regarding the accuracy, completeness, or timeliness of the content and is not responsible for any actions taken based on the information provided. The content does not constitute financial, legal, or other professional advice, nor should it be considered a recommendation or endorsement by MEXC.

You May Also Like

Kraken's Big Hint: Pi Coin Set for Exchange Listing In 2026

Pi Coin (PI) is deeply embarked in the ongoing red light therapy that’s crunched the global crypto’s market capitalization below $2.4 trillion. The mobile mining

Share

Coinstats2026/02/07 09:25

US Stock Market Could Double By End Of Presidential Term

The post US Stock Market Could Double By End Of Presidential Term appeared on BitcoinEthereumNews.com. Trump’s Bold Prediction: US Stock Market Could Double By

Share

BitcoinEthereumNews2026/02/07 10:43

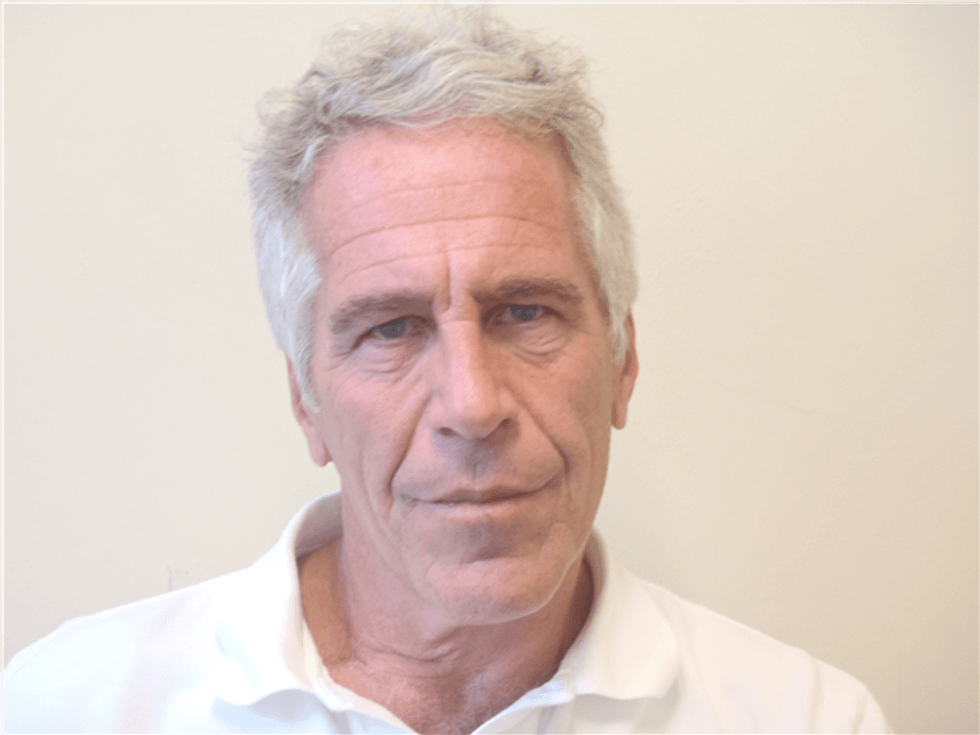

Trump official bought business with Epstein years after claiming to cut ties: report

Before he joined President Donald Trump's Cabinet, Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick jointly owned a business with convicted child predator Jeffrey Epstein.CBS

Share

Alternet2026/02/07 10:32