Quadro RW and Cryptocurrencies: Why Tax Monitoring Isn’t Designed for the Crypto World

The RW framework has become, in recent years, one of the most debated tools in the tax management of cryptocurrencies in Italy. Originally designed to monitor financial assets held abroad, it is now also used for crypto-assets, but often with controversial results.

According to Stefano Capaccioli, the issue is not only applicative but structural: the RW framework was not designed for a decentralized ecosystem like that of cryptocurrencies.

Why the RW Framework Exists

To understand the current issues, it is necessary to start from its origin. The RW framework was established during the years when Italy had strict currency restrictions. With the liberalization of capital movements and entry into the European Union, the State relinquished prior control over foreign accounts, replacing it with a communication obligation.

The objective was simple: to know what taxpayers held abroad, in a context where the tax administration did not have direct access to the information.

A system designed for traditional finance

The RW framework works relatively well when it comes to bank accounts, securities deposits, stored gold, or financial investments. In all these cases, there exists:

- an intermediary,

- a jurisdiction,

- an easily determinable value.

Cryptocurrencies, however, break this pattern.

Wallet does not mean “container”

One of the most common conceptual errors concerns the wallet. In the interpretation of the financial administration, the wallet is often equated to a portfolio that “contains” cryptocurrencies.

In reality, as highlighted by Capaccioli, the wallet contains nothing. It is a tool for managing cryptographic keys and digital identities. Crypto-assets reside on the blockchain, not in the wallet. This already weakens the idea of linking monitoring to a location or physical custody.

The Year-End Value Issue

Another critical issue concerns the obligation to indicate the value of crypto-assets as of December 31. While for Bitcoin, Ether, or stablecoins this value is easily obtainable, the same does not apply to thousands of illiquid tokens, airdrops, or assets lacking a reference market.

In many cases, assigning a value is impossible or arbitrary. Yet, the obligation to monitor remains, exposing the taxpayer to the risk of future disputes.

Monitoring also on Italian intermediaries

The current regulation requires the inclusion of cryptocurrencies held with Italian intermediaries in the RW framework. This represents an additional anomaly: the monitoring was designed to compensate for the lack of information, but in the case of Italian exchanges, the data is already available to the administration.

With the introduction of automatic information exchange mechanisms, such as those provided at the European level, the original function of the RW framework appears increasingly unjustified.

A Tool to Rethink

According to Capaccioli, the extension of the RW framework to crypto-assets risks becoming a disproportionate and ineffective requirement. Without a thorough revision, tax monitoring will continue to clash with the very nature of cryptocurrencies, generating more uncertainty than actual control.

You May Also Like

The author of "Rich Dad Poor Dad" responds to criticism: He will continue to increase his holdings of Bitcoin and gold; investors should focus on asset value.

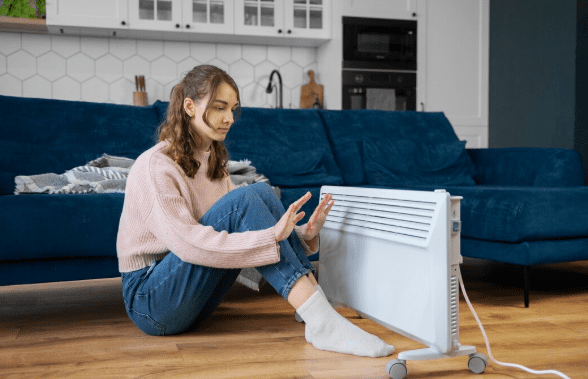

Space Heaters Explained: How They Work and When to Use Them