How Inductive Scratchpads Help Transformers Learn Beyond Their Training Data

Table of Links

Abstract and 1. Introduction

1.1 Syllogisms composition

1.2 Hardness of long compositions

1.3 Hardness of global reasoning

1.4 Our contributions

-

Results on the local reasoning barrier

2.1 Defining locality and auto-regressive locality

2.2 Transformers require low locality: formal results

2.3 Agnostic scratchpads cannot break the locality

-

Scratchpads to break the locality

3.1 Educated scratchpad

3.2 Inductive Scratchpads

-

Conclusion, Acknowledgments, and References

A. Further related literature

B. Additional experiments

C. Experiment and implementation details

D. Proof of Theorem 1

E. Comment on Lemma 1

F. Discussion on circuit complexity connections

G. More experiments with ChatGPT

\

3 Scratchpads to break the locality

Prior literature. It has been shown that training Transformers with the intermediate steps required to solve a problem can enhance learning. This idea is usually referred to as providing models with a scratchpad [32]. The improved performance due to scratchpads has been reported on a variety of tasks including mathematical tasks and programming state evaluation [32, 11, 17]. See Appendix A for further references.

3.1 Educated scratchpad

\

\

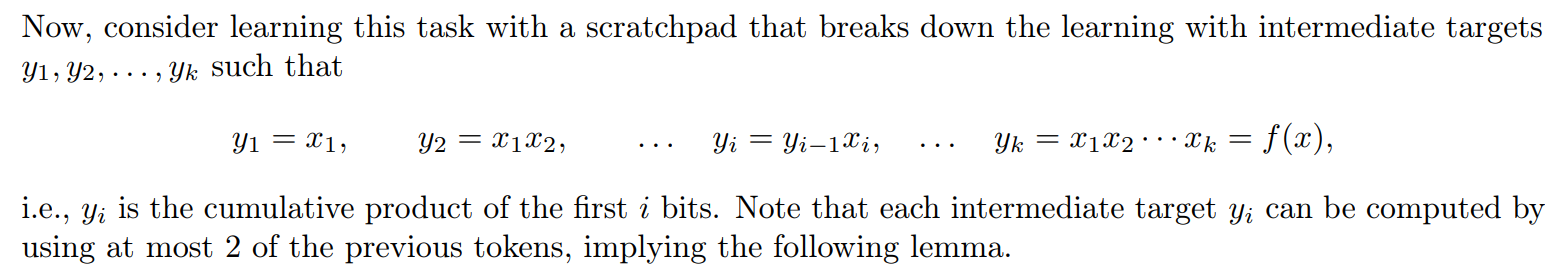

\ Lemma 2. The parity task with the cumulative product scratchpad has a locality of 2.

\ Transformers with such a scratchpad can in fact easily learn parity targets, see Appendix B.3.

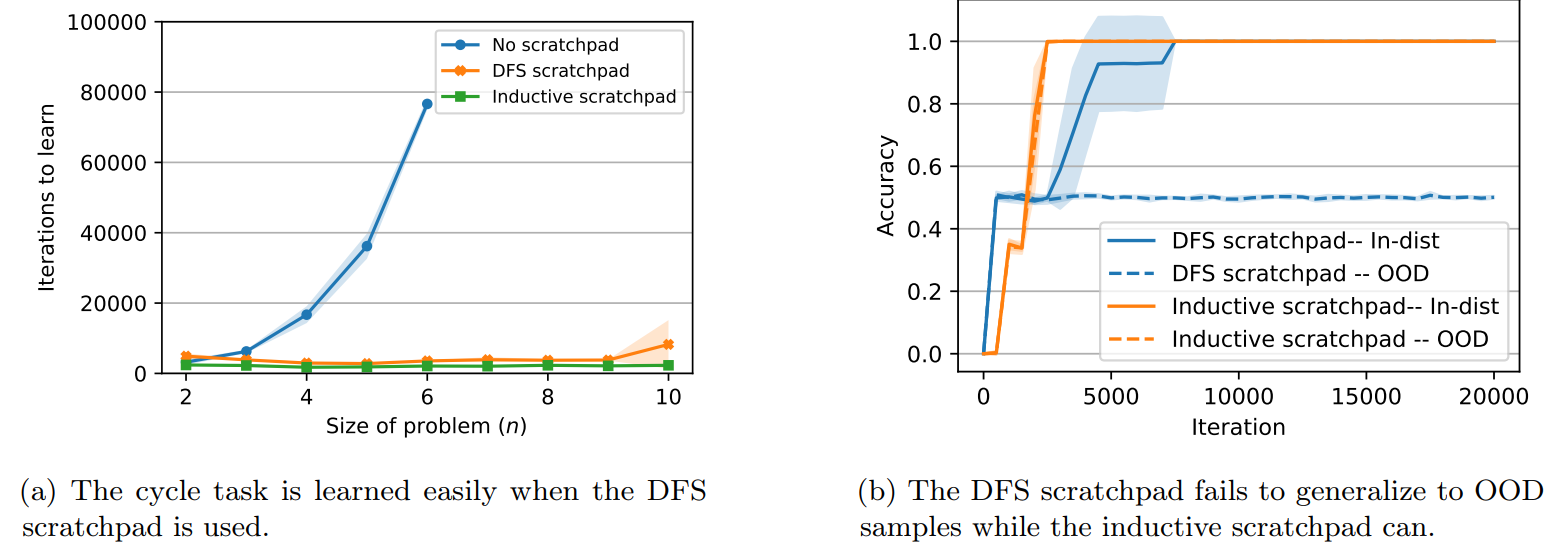

\ Results for the cycle task. Consider the cycle task and a scratchpad that learns the depth-first search (DFS) algorithm from the source query node.[9] For example, consider the following input corresponding to two cycles a, x, q and n, y, t: a>x; n>y; q>a; t>n; y>t; x>q; a?t;. In this case, doing a DFS from node a gives a>x>q>a where the fact that we have returned to the source node a and not seen the destination t indicates that the two nodes are not connected. Therefore, the full scratchpad with the final answer can be designed as a>x>q>a;0. Similarly, if the two nodes were connected the scratchpad would be a>…>t;1. One can easily check that the cycle task becomes low-locality with the DFS scratchpad.

\ Lemma 3. The cycle task with the DFS scratchpad has a locality of 3.

\ This follows from the fact that one only needs to find the next node in the DFS path (besides the label), which one can check with polynomial chance by checking the first edge.

\ In Figure 4a we show that a decoder-only Transformer with the DFS scratchpad in fact learns the cycle task when n scales.

\ Remark 4. If one has full knowledge of the target function, one could break the target into sub-targets using an educated scratchpad to keep the locality low and thus learn more efficiently (of course one does not have to learn the target under full target knowledge, but one may still want to let a model learn it to develop useful representations in a broader/meta-learning context). One could in theory push this to learning any target that is poly-time computable by emulating a Turing machine in the steps of the scratchpad to keep the overall locality low. Some works have derived results in that direction, such as [33] for some type of linear autoregressive models, or [12] for more abstract neural nets that emulate any Turing machine with SGD training. However, these are mostly theory-oriented works. In practice, one may be instead interested in devising a more ‘generic’ scratchpad. In particular, a relevant feature in many reasoning tasks is the power of induction. This takes place for instance in the last 2 examples (parity and cycle task) where it appears useful to learn inductive steps when possible.

3.2 Inductive Scratchpads

As discussed previously, scratchpads can break the local reasoning barrier with appropriate mid-steps. In this part, however, we show that fully educated scratchpads can be sensitive to the number of reasoning steps, translating into poor out-of-distribution (OOD) generalization. As a remedy, we put forward the concept of inductive scratchpad which applies to a variety of reasoning tasks as in previous sections.

\ 3.2.1 Educated scratchpad can overfit in-distribution samples

\ Consider the cycle task with 40 nodes. For the test distribution, we use the normal version of the cycle task, i.e., either two cycles of size 20 and the nodes are not connected or a single cycle of size 40 where the distance between the query nodes is 20. For the train distribution, we keep the same number of nodes and edges (so the model does not need to rely on new positional embeddings for the input) but break the cycles to have uneven lengths: (1) a cycle of size 10 and a cycle of size 30 when the two nodes are not connected (the source query node is always in the cycle of size 10) or (2) a cycle of size 40 where the nodes are at distance[10]. Thus, in general, we always have 40 nodes/edges in the graphs. However, the length of the DFS path (i.e., number of reasoning steps) is 10 at training and 20 at test. We trained our model on this version of the task with the DFS scratchpad. The results are shown in Figure 4b. We observe that the model quickly achieves perfect accuracy on the training distribution, yet, it fails to generalize OOD as the model overfits the scratchpad length. In the next part, we introduce the notion of inductive scratchpad to fix this problem.

\ 3.2.2 Inductive scratchpad: definition and experimental results

\ In a large class of reasoning tasks, one can iteratively apply an operation to some state variable (e.g., a state array) to compute the output. This applies in particular to numerous graph algorithms (e.g., shortest path algorithms such as BFS or Dijkstra’s algorithm), optimization algorithms (such as genetic algorithms or gradient descent), and arithmetic tasks.

\ Definition 5 (Inductive tasks). Let Q be the question (input). We say that a task can be solved inductively when there is an induction function (or a state transition function) g such that

\ s[1] = g(Q, ∅), s[2] = g(Q, s[1]), . . . , s[k] = g(Q, s[k − 1]),

\ where s[1], . . . , s[k] are the steps (or states) that are computed inductively. For example, the steps/states could be an array or the state of an automata that is being updated. Note that the termination is determined by the state. In the context of Transformers, one can use the generation of the end of sequence token to terminate.

\ Inductive tasks with a fully educated scratchpad can overfit proofs. The fully educated scratchpad for the question Q as input would be s[1];s[2];…;s[k], where the token ends the generation. However, this method may not fully utilize the fact that each state is only generated from the last state by applying the same (set of) operation(s). In particular, s[k] typically attends to all of the previous states. Further, the model may not be able to increase the number of induction steps beyond what it has seen during training, as shown in Figure 4b for the cycle task.

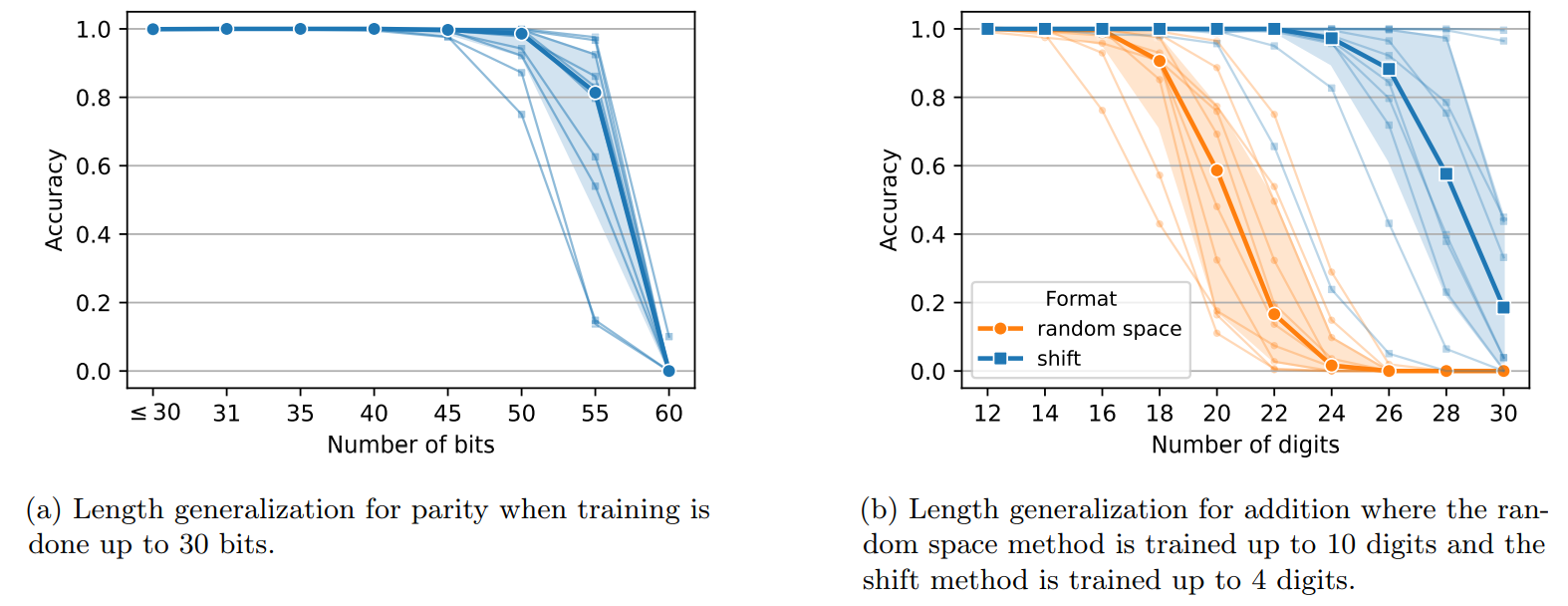

\ Now we show that by using attention masking and reindexing the positions of the tokens, one can promote the desired ‘inductive’ behavior. We call this the inductive scratchpad. As three showcases, we demonstrate that the inductive scratchpad can improve OOD generalization on the cycle task and length generalization on parity and addition tasks.

\ Inductive scratchpad implementation. The inductive scratchpad for an inductive task is similar in format to the fully educated scratchpad but it has the following modifications: (1) tokens: two new special tokens are used: the token which separates the question from the intermediate states and

\

\ the token (denoted # hereafter) to separate the states. Using these tokens, for an input question Q, the format of the inductive scratchpad reads s[1]#s[2]#…#s[k]. (2) generation: we want the model to promote induction and thus ‘forget’ all the previous states except the last one for the new state update. I.e., we want to generate tokens of s[i+1] as the input was Qs[i]#. To implement this, one can use attention masking and reindex positions (in order to have a proper induction) or simply remove the previous states at each time; (3) training: when training the scratchpad, we want the model to learn the induction function g, i.e., learning how to output s[i+1]# from Q s[i]#, which can be achieved with attention masking and reindexing the positions. As a result, the inductive scratchpad can be easily integrated with the common language models without changing their behavior on other tasks/data. We refer to Appendix C.2 for a detailed description of the inductive scratchpad implementation.

\ Inductive scratchpad for the cycle task. The DFS scratchpad of the cycle task can be made inductive by making each step of the DFS algorithm a state. E.g., for the input a>x;n>y;q>a;t>n;y>t; x>q;a?t;, the DFS scratchpad is a>x>q>a;0, and the inductive scratchpad becomes a#x#q#a;0*<EOS>* where each state tracks the current node in the DFS. In Figure 4b, we show that the inductive scratchpad for the cycle task can generalize to more reasoning steps than what is seen during training, and thus generalize OOD when the distance between the nodes is increased.

\ Length generalization for parity and addition tasks. We can use inductive scratchpads to achieve length generalization for the parity and addition tasks. For parities, we insert random spaces between the bits and design an inductive scratchpad based on the position of the bits and then compute the parity iteratively. Using this scratchpad we can train a Transformer on up to 30 bits and get generalization on up to 50, or 55 bits. Results are provided in Figure 5a. For the addition task, we consider two inductive scratchpad formats. We provide an inductive scratchpad that requires random spaces between the digits in the input and uses the position of the digits to compute the addition digit-by-digit (similar to the parity). With this scratchpad, we can generalize to numbers with 20 digits while training on numbers with up to 10 digits. In the other format, we use random tokens in the input and we compute the addition digit-by-digit by shifting the operands. The latter enables us to generalize from 4 to 26 digits at the cost of having a less natural input format. The results for different seeds are provided in Figure 5b. See details of these scratchpads in Appendices B.4, B.5. 10 Also see Appendix A for a comparison with recent methods.

\

:::info Authors:

(1) Emmanuel Abbe, Apple and EPFL;

(2) Samy Bengio, Apple;

(3) Aryo Lotf, EPFL;

(4) Colin Sandon, EPFL;

(5) Omid Saremi, Apple.

:::

:::info This paper is available on arxiv under CC BY 4.0 license.

:::

[9] For the particular graph structure of the two cycles task, DFS is the same as the breadth-first search (BFS).

\ [10] Our code is also available at https://github.com/aryol/inductive-scratchpad.

You May Also Like

Ripple Buyers Step In at $2.00 Floor on BTC’s Hover Above $91K

Jamie Dimon Says He Doesn't Like 'Debanking People,' Denies Targeting Trump Media: 'People Have To Grow Up'