Calibration of Radio Polarization Data: Enhancing Correlation Between CHIME and Dwingeloo Surveys

Table of Links

Abstract and 1 Introduction

-

Faraday Rotation and Faraday Synthesis

-

Dara & Instruments

3.1. CHIME and GMIMS surveys and 3.2. CHIME/GMIMS Low Band North

3.3. DRAO Synthesis Telescope Observations

3.4. Ancillary Data Sources

-

Features of the Tadpole

4.1. Morphology in single-frequency images

4.2. Faraday depths

4.3. Faraday complexity

4.4. QU fitting

4.5. Artifacts

-

The Origin of the Tadpole

5.1. Neutral Hydrogen Structure

5.2. Ionized Hydrogen Structure

5.3. Proper Motions of Candidate Stars

5.4. Faraday depth and electron column

-

Summary and Future Prospects

\ APPENDIX

A. RESOLVED AND UNRESOLVED FARADAY COMPONENTS IN FARADAY SYNTHESIS

B. QU FITTING RESULTS

\ REFERENCES

3.1. CHIME and GMIMS surveys

3.2. CHIME/GMIMS Low Band North

\

\ The ringmaps we use do not have beam deconvolution applied. There are small artifacts in the image resulting from this which we describe in Section 4.5, however, their presence is not detrimental to studying structures on the scale of several degrees, such as the tadpole. In this analysis, we use the 400 − 729 MHz subset of the full CHIME band, as the highest frequencies are contaminated by aliasing, which makes the maps unreliable in the region of interest.

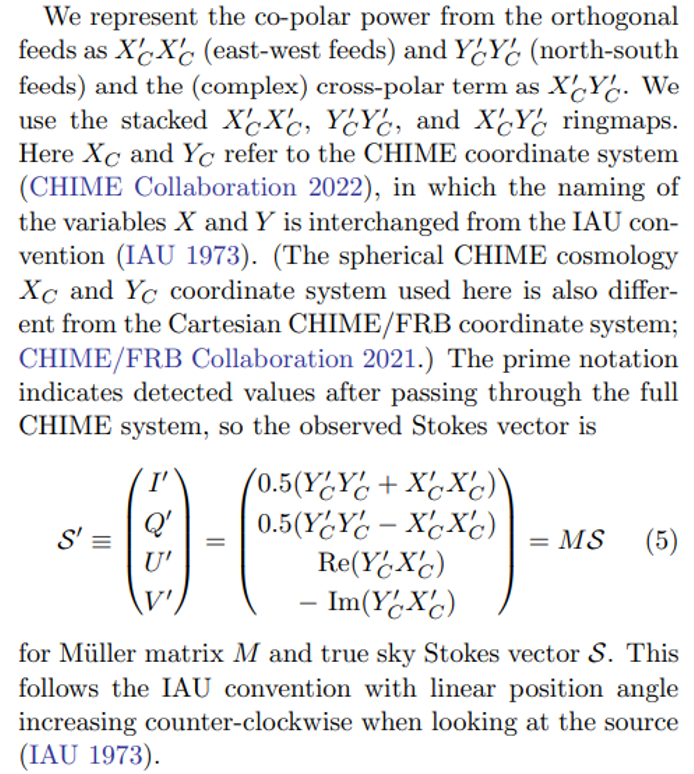

\ 3.2.1. Polarization angle calibration

\

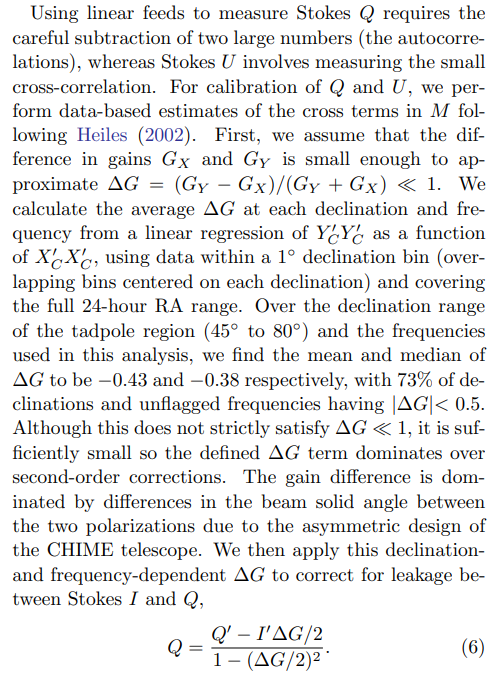

\

\

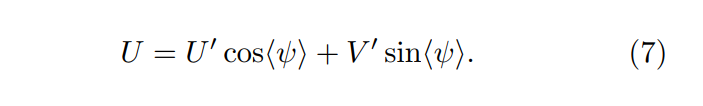

\ Stokes U and V are measured from the crosscorrelation products. We assume that ⟨V ⟩ = 0 from the sky in diffuse emission because synchrotron emission in low-density astrophysical environments does not produce circular polarization. Leakage between V and U arises from phase offsets. We measure a mean phase shift ⟨ψ⟩(δ, ν) at each declination and frequency assuming that ⟨V ⟩ = 0 and calculate

\

\ The ⟨V ⟩ = 0 assumption leads to high-quality fits even in fast radio burst (FRB) observations, where the assumption has less clear physical justification than in the diffuse polarized emission we investigate (Mckinven et al. 2023). We find that the phase shift is linear in frequency, consistent with a cable delay τ = ⟨ψ⟩/2πν ∼ 1 ns for the diffuse emission, as Mckinven et al. (2021, their Appendix A) found in CHIME/FRB data.

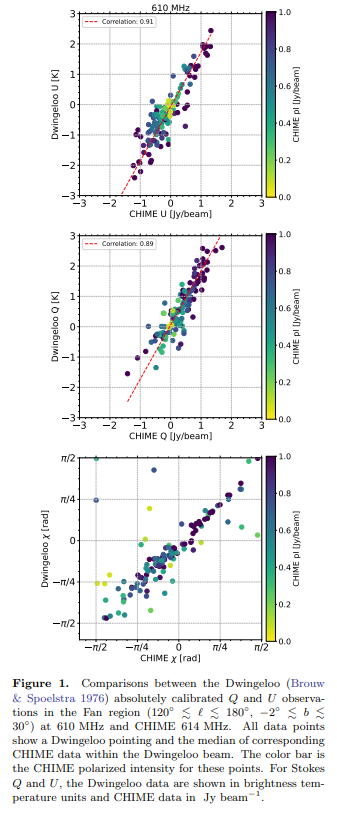

\ In Figure 1, we compare the calibrated data to the Dwingeloo telescope survey at 610 MHz in the Fan region (Brouw & Spoelstra 1976). There is a strong correlation between Dwingeloo U and CHIME U and Dwingeloo Q and CHIME Q in those directions for which there is Dwingeloo data, with correlation coefficient R values of 0.91 for U − U and 0.89 for Q − Q comparisons. This is a significant improvement from the uncalibrated correlation coefficients of 0.76 and 0.59 respectively. We find a remaining leakage of up to 20% in Stokes Q based on unresolved point source measurements. Using the mean orthogonal distance between each point and the fitted line, we find that noise from CHIME and Dwingeloo data describe ≈ 70% of the scatter in Figure 1. The polarization angle correlation, also shown in Figure 1, is also improved through calibration, and most outliers are points with low polarized intensity (yellow dots), where the uncertainty in derived χ is high.

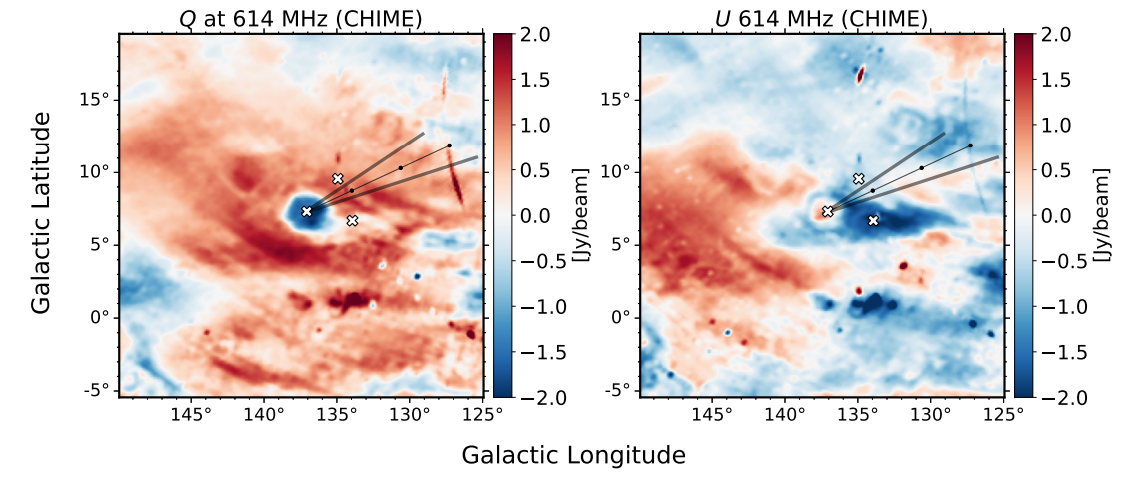

\ We show the resulting CHIME Q and U maps, with the χ = 0 reference axis rotated to the north Galactic pole, in Figure 2. While Stokes I to Q leakage does exist in our data, the tadpole structure cannot simply be the result of leakage. Although there is total intensity emission over the entire Fan Region, including the tadpole, this emission is featureless on small scales and thus cannot produce spurious polarization matching the tadpole in morphology. Furthermore, the tadpole cannot be the product of Stokes I emission originating at large angular distances (such as the Galactic plane) and seen in far sidelobes. While the far sidelobes have poor polarization properties, their polarization averages to low values over sizable areas. Moreover, with linear feeds, leakage from I is primarily into Q, not U (in the native equatorial coordinates of CHIME), but the tadpole is already evident in Stokes U in equatorial coordinates (not shown).

\

\

\ 3.2.2. Faraday synthesis on CHIME data

\

\

\ Using the rmtools_peakfitcube algorithm in RM-Tools, we obtain the peak Faraday depth and its

\

\ associated error for every spectrum along all lines of sight. The resulting map is shown in Figure 3b. We use peak Faraday depths rather than a first moment (Dickey et al. 2019) to focus on the Faraday depth of the brightest feature in each LOS rather than a weighted mean Faraday depth in Faraday complex regions.

\ We show the integrated polarized intensity across the Faraday depth spectra as a zero moment map in Figure 3a. A polarization angle map derotated to χ0 by the peak Faraday depth at each pixel is shown in Figure 3c.

\

:::info Authors:

(1) Nasser Mohammed, Department of Computer Science, Math, Physics, & Statistics, University of British Columbia, Okanagan Campus, Kelowna, BC V1V 1V7, Canada and Dominion Radio Astrophysical Observatory, Herzberg Research Centre for Astronomy and Astrophysics, National Research Council Canada, PO Box 248, Penticton, BC V2A 6J9, Canada;

(2) Anna Ordog, Department of Computer Science, Math, Physics, & Statistics, University of British Columbia, Okanagan Campus, Kelowna, BC V1V 1V7, Canada and Dominion Radio Astrophysical Observatory, Herzberg Research Centre for Astronomy and Astrophysics, National Research Council Canada, PO Box 248, Penticton, BC V2A 6J9, Canada;

(3) Rebecca A. Booth, Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Calgary, 2500 University Drive NW, Calgary, Alberta, T2N 1N4, Canada;

(4) Andrea Bracco, INAF – Osservatorio Astrofisico di Arcetri, Largo E. Fermi 5, 50125 Firenze, Italy and Laboratoire de Physique de l’Ecole Normale Superieure, ENS, Universit´e PSL, CNRS, Sorbonne Universite, Universite de Paris, F-75005 Paris, France;

(5) Jo-Anne C. Brown, Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Calgary, 2500 University Drive NW, Calgary, Alberta, T2N 1N4, Canada;

(6) Ettore Carretti, INAF-Istituto di Radioastronomia, Via Gobetti 101, 40129 Bologna, Italy;

(7) John M. Dickey, School of Natural Sciences, University of Tasmania, Hobart, Tas 7000 Australia;

(8) Simon Foreman, Department of Physics, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ 85287, USA;

(9) Mark Halpern, Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of British Columbia, 6224 Agricultural Road, Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z1 Canada;

(10) Marijke Haverkorn, Department of Astrophysics/IMAPP, Radboud University, PO Box 9010, 6500 GL Nijmegen, The Netherlands;

(11) Alex S. Hill, Department of Computer Science, Math, Physics, & Statistics, University of British Columbia, Okanagan Campus, Kelowna, BC V1V 1V7, Canada and Dominion Radio Astrophysical Observatory, Herzberg Research Centre for Astronomy and Astrophysics, National Research Council Canada, PO Box 248, Penticton, BC V2A 6J9, Canada;

(12) Gary Hinshaw, Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of British Columbia, 6224 Agricultural Road, Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z1 Canada;

(13) Joseph W. Kania, Department of Physics and Astronomy, West Virginia University, P.O. Box 6315, Morgantown, WV 26506, USA and Center for Gravitational Waves and Cosmology, West Virginia University, Chestnut Ridge Research Building, Morgantown, WV 26505, USA;

(14) Roland Kothes, Dominion Radio Astrophysical Observatory, Herzberg Research Centre for Astronomy and Astrophysics, National Research Council Canada, PO Box 248, Penticton, BC V2A 6J9, Canada;

(15) T.L. Landecker, Dominion Radio Astrophysical Observatory, Herzberg Research Centre for Astronomy and Astrophysics, National Research Council Canada, PO Box 248, Penticton, BC V2A 6J9, Canada;

(16) Joshua MacEachern, Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of British Columbia, 6224 Agricultural Road, Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z1 Canada;

(17) Kiyoshi W. Masui, MIT Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 77 Massachusetts Ave, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA and Department of Physics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 77 Massachusetts Ave, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA;

(18) Aimee Menard, Department of Computer Science, Math, Physics, & Statistics, University of British Columbia, Okanagan Campus, Kelowna, BC V1V 1V7, Canada and Dominion Radio Astrophysical Observatory, Herzberg Research Centre for Astronomy and Astrophysics, National Research Council Canada, PO Box 248, Penticton, BC V2A 6J9, Canada;

(19) Ryan R. Ransom, Dominion Radio Astrophysical Observatory, Herzberg Research Centre for Astronomy and Astrophysics, National Research Council Canada, PO Box 248, Penticton, BC V2A 6J9, Canada and Department of Physics and Astronomy, Okanagan College, Kelowna, BC V1Y 4X8, Canada;

(20) Wolfgang Reich, Max-Planck-Institut fur Radioastronomie, Auf dem Hugel 69, 53121 Bonn, Germany;(21) Patricia Reich, 16

(22) J. Richard Shaw, Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of British Columbia, 6224 Agricultural Road, Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z1 Canada

(23) Seth R. Siegel, Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics, 31 Caroline Street N, Waterloo, ON N25 2YL, Canada, Department of Physics, McGill University, 3600 rue University, Montreal, QC H3A 2T8, Canada, and Trottier Space Institute, McGill University, 3550 rue University, Montreal, QC H3A 2A7, Canada;

(24) Mehrnoosh Tahani, Banting and KIPAC Fellowships: Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics & Cosmology (KIPAC), Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305, USA;

(25) Alec J. M. Thomson, ATNF, CSIRO Space & Astronomy, Bentley, WA, Australia;

(26) Tristan Pinsonneault-Marotte, Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of British Columbia, 6224 Agricultural Road, Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z1 Canada;

(27) Haochen Wang, MIT Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 77 Massachusetts Ave, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA and Department of Physics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 77 Massachusetts Ave, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA;

(28) Jennifer L. West, Dominion Radio Astrophysical Observatory, Herzberg Research Centre for Astronomy and Astrophysics, National Research Council Canada, PO Box 248, Penticton, BC V2A 6J9, Canada;

(29) Maik Wolleben, Skaha Remote Sensing Ltd., 3165 Juniper Drive, Naramata, BC V0H 1N0, Canada.

:::

:::info This paper is available on arxiv under CC BY 4.0 DEED license.

:::

\

Ayrıca Şunları da Beğenebilirsiniz

Historic Debut: U.S. Sees Launch of Spot ETFs for DOGE and XRP

Now You Don’t’ New On Streaming This Week, Report Says